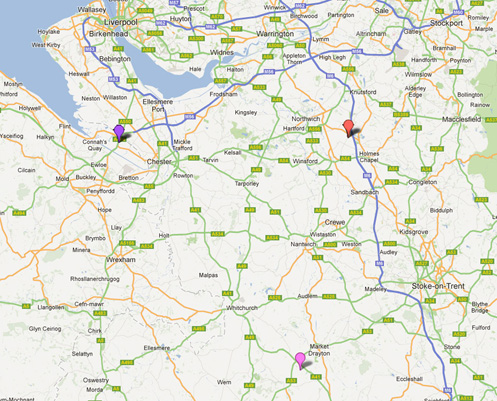

The School of General Reconnaissance was formed pre-WWI and was stationed at R.A.F. Manston, Kent [green marker]. Over time the role of the School changed and it became the No.2 School of Air Navigation [No.2 S.o.A.N.] in January 1936, remaining at Manston until September 1939 when the airfield was needed for Fighter Command, 11 Group. Being a training school it was decided that No.2 S.o.A.N. should be moved out of the reach of the Luftwaffe. It was thought that St. Athan, South Wales [orange marker] would be ideal, but as the German forces progressed across France, it quickly became apparent that this was not going to be the case. On 18 October 1940 the first three Avro Anson flew to their new home approximately 133 miles further north. Construction of the buildings was still under way, the runways were grass [and mud] and it wouldn’t be long before the weather took a turn for the worse. Welcome to R.A.F. Cranage [red marker].

The School of General Reconnaissance was formed pre-WWI and was stationed at R.A.F. Manston, Kent [green marker]. Over time the role of the School changed and it became the No.2 School of Air Navigation [No.2 S.o.A.N.] in January 1936, remaining at Manston until September 1939 when the airfield was needed for Fighter Command, 11 Group. Being a training school it was decided that No.2 S.o.A.N. should be moved out of the reach of the Luftwaffe. It was thought that St. Athan, South Wales [orange marker] would be ideal, but as the German forces progressed across France, it quickly became apparent that this was not going to be the case. On 18 October 1940 the first three Avro Anson flew to their new home approximately 133 miles further north. Construction of the buildings was still under way, the runways were grass [and mud] and it wouldn’t be long before the weather took a turn for the worse. Welcome to R.A.F. Cranage [red marker].

Those three aircraft were not the first aircraft to use Cranage [red marker], that title went to the Airspeed Oxford, Hawker Hind & Miles Master aircraft of No.5 Flying Training School [No.5 F.T.S.] at Sealand [purple marker] who flew to and from the airfield between the end of May and the beginning of September 1940. Flights from the school would make use of the airfield during the day, before returning to Sealand in the evening, it is thought that some of these pilots practised their night flying skills on the return flight. From late July through into September, the airfield was also used by Avro Anson and North American Aviation Harvard aircraft of No.10 F.T.S., Tern Hill [pink marker].

Those three aircraft were not the first aircraft to use Cranage [red marker], that title went to the Airspeed Oxford, Hawker Hind & Miles Master aircraft of No.5 Flying Training School [No.5 F.T.S.] at Sealand [purple marker] who flew to and from the airfield between the end of May and the beginning of September 1940. Flights from the school would make use of the airfield during the day, before returning to Sealand in the evening, it is thought that some of these pilots practised their night flying skills on the return flight. From late July through into September, the airfield was also used by Avro Anson and North American Aviation Harvard aircraft of No.10 F.T.S., Tern Hill [pink marker].

Below - orange dates indicate a Cranage accident, green dates indicate an encounter with the enemy.

During those early months the accident and death rate was high both in and around the airfield at Cranage.

27 July, Miles Master N7759 suffered engine failure shortly after take off for a night flying exercise. The pilot made an attempt to return to the airfield but two miles short of the airfield, at Rudheath, he hit a tree, writing off the aircraft. Fortunately the pilot survived.

8 August, the pilot of Miles Master N7714 was not so lucky. The plane 'swung' on take off, clipped some cables and crashed.

5 September, during a night flying exercise, Miles Master N7921 strayed from the circuit, crashing into the the roof of a house killing the pilot.

11 September, while taking off on another night time exercise, Miles Master N7571 skidded, crashed and caught fire killing the pilot.

27 September, Miles Master N7759, undershot on a night landing, clipped some trees and crashed killing the pilot

On Monday, 21 October 1940, the school was officially formed with Wing Commander R. J. Cooper as the Commanding Officer. The primary aim of the school was to offer advanced training to experienced pilots and navigators in air navigation, especially celestial (night) navigation. Courses ranged from a few weeks to a few months, with some lasting almost a year, courses such as Air Observers Instructors; Captains of Aircraft; Specialist Navigator; Airborne Interception Navigators; Staff Navigation Instructors; under training Air Observers (WT) and Air Observers Elementary.

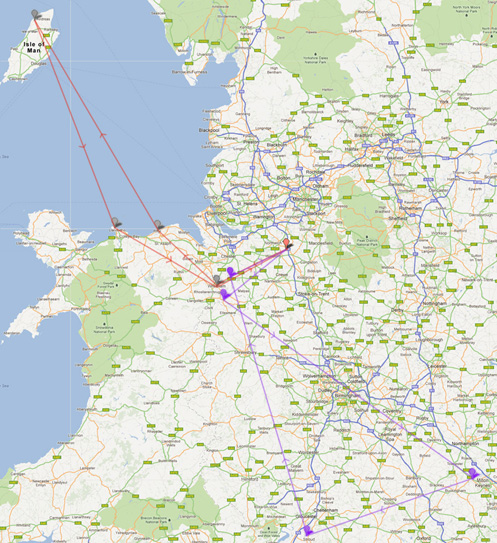

Simple triangular navigation exercise routes flown included DR5/R54 (DR - Dead Reckoning), Cranage -to- Wrexham -to- Rhyl -to- Jurby (Isle of Man) -to- the Great Orme -to- Wrexham -to- Cranage [red route], a flight time of just over 2 hours, and DR3/R6, Cranage -to- Overton -to- Stony Stratford -to- Ludlow Green -to- Holt -to- Cranage [purple route], a flight time of 2 hours 45 minutes.

Simple triangular navigation exercise routes flown included DR5/R54 (DR - Dead Reckoning), Cranage -to- Wrexham -to- Rhyl -to- Jurby (Isle of Man) -to- the Great Orme -to- Wrexham -to- Cranage [red route], a flight time of just over 2 hours, and DR3/R6, Cranage -to- Overton -to- Stony Stratford -to- Ludlow Green -to- Holt -to- Cranage [purple route], a flight time of 2 hours 45 minutes.

From talking to Stan Pascoe [see Stan's information in the Personnel section] one of the long range exercises would take in a DR leg to Rockall [that tiny speck of rock out in the North Atlantic] before landing at RAF Benbecula [North Uist] to re-fuel, then returning to Cranage as a night flight, total flying about 8 hours. This type of exercise was in the latter part of the course when the trainees were virtually qualified.

From talking to Stan Pascoe [see Stan's information in the Personnel section] one of the long range exercises would take in a DR leg to Rockall [that tiny speck of rock out in the North Atlantic] before landing at RAF Benbecula [North Uist] to re-fuel, then returning to Cranage as a night flight, total flying about 8 hours. This type of exercise was in the latter part of the course when the trainees were virtually qualified.

Ground instruction commenced the day the School was formed with 10 pilots who had already started at St.Athan, but had had their training disrupted by the move, and another 44 Ansons arrived from St.Athan. One week later No.8 Instructors Course started. The School was made up from 174 Officers, 720 NCOs’, and airmen including 61 civilians.

With more new aircraft arriving at the School and the inevitable accident rate climbing, repairs were an immediate necessity for the schools Anson and Oxford aircraft, this was undertaken by Air Taxis Limited, Barton, Lancashire.

Frost and snow descended on Cranage from November onwards. These conditions meant that construction work was at best slow and quite often cancelled. Wing Commander Gerry Roberts was a Sergeant at the time and he recalls the Sergeant's quarters as cramped and without hot water, mainly because no one wanted to spend the time lighting fires under the tureens that were supplied for that very purpose and it was easier, if a little more hazardous, to plug heaters into the light sockets. Other personnel who were there at the time remember sleeping on or under the pews in nearby Byley church.

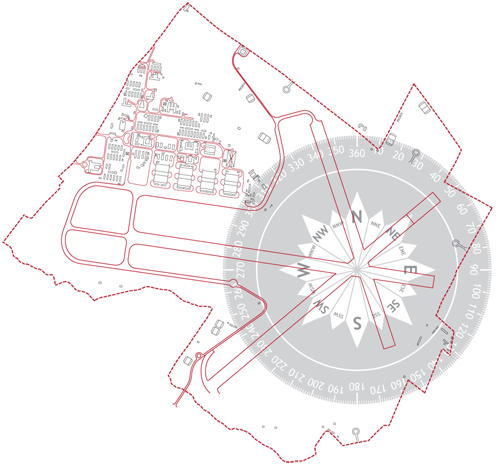

As the School grew the number of operating Ansons quickly grew to 70, which was too many for such a small airfield. Although it really should have had 'hard' runways, Cranage was never to receive them, instead it had three grass runways - 10/28 [shown as 2/5 on the site plan] at 3,860 feet, 05/23 [shown as 1/4 on the site plan] at 3,240 feet and 16/34 [shown as 3/6 on the site plan] at 3,000 feet, mostly linked by cinder taxiway. The surface of both was covered by Sommerfeld Track to help take the weight of the aircraft though this was soon replaced with Pierced Steel Plate [Marsden Matting]. The code allocated to RAF Cranage was 4XCR.

As the School grew the number of operating Ansons quickly grew to 70, which was too many for such a small airfield. Although it really should have had 'hard' runways, Cranage was never to receive them, instead it had three grass runways - 10/28 [shown as 2/5 on the site plan] at 3,860 feet, 05/23 [shown as 1/4 on the site plan] at 3,240 feet and 16/34 [shown as 3/6 on the site plan] at 3,000 feet, mostly linked by cinder taxiway. The surface of both was covered by Sommerfeld Track to help take the weight of the aircraft though this was soon replaced with Pierced Steel Plate [Marsden Matting]. The code allocated to RAF Cranage was 4XCR.

Sommerfeld Tracking is named after the German expatriate engineer, Kurt Joachim Sommefeld who was a living in England. It is a lightweight wire mesh stiffened laterally by steel rods, giving it a good load carrying capacity while allowing it to be rolled up for storage or transportation. Rolls were 10’8” [3.25m] wide by 75’6” [23m] long and the steel rods were inserted every 9” [22.8cm]. Construction would have been coir [coconut matting], to help combat the mud, then the tracking would be laid out and pulled tight using horses, steam rollers or tractors then fastened to the ground with angle-iron pickets with each of the track joined together by use of a long flat steel bar through loops in the ends of the steel rods. During heavy rainfall this surface proved to be dangerous to aircraft taking off and or landing and so there were days where nothing flew in or out of Cranage.

P.S.P. consisted of steel strips with holes punched through it in rows and a formation of U-shaped channels between the holes. Hooks were formed along one edge and slots along the other so that they could be connected together in a staggered pattern, similar to that of brick work. The hooks were usually held in the slots by a steel clip that filled the part of the slot that is empty when the adjacent sheets are properly engaged together. The holes were bent up at their edges so that the beveled edge stiffened the area around the hole. In some mats a T-shaped stake could be driven, at intervals, through the holes to keep the assembly in place on the ground. Sometimes the sheets were welded together. The typical Marsden matting was the M8 landing mat. A single piece weighed about 66 pounds and was 10 ft (3.0 m) long by 15 in (0.38 m) wide. The hole pattern for the sheet was three holes wide by 29 holes long resulting in 87 holes per mat. A variation made from aluminium was produced to allow easier transportation by aircraft, since it weighed about 2/3 as much. It was referred to as PAP for perforated aluminium planking, but was not as common as aluminium was a controlled strategic material during WWII.

This section of P.S.P. from R.A.F. Cranage was spotted by ‘Tigger’ when we had a look round the farm land that was once the airfield. I popped back a couple of days later and with kind permission of Brian Lowe, who’s family own some of the land, I recovered this piece and a Screw Tie.

This section of P.S.P. from R.A.F. Cranage was spotted by ‘Tigger’ when we had a look round the farm land that was once the airfield. I popped back a couple of days later and with kind permission of Brian Lowe, who’s family own some of the land, I recovered this piece and a Screw Tie.

When the German invasion commenced in May 1940, 85 Squadron found itself locked in battle with the Luftwaffe, and with attacks on its aerodromes commonplace there was no respite from operations. In an eleven day period the squadron had accounted for a confirmed total of 90 enemy aircraft. The final sorties saw the squadron giving fighter cover to the Allied armies until its bases were finally overrun and the three remaining aircraft retired to the UK. The squadron re-equipped and resumed full operations early in June 1940. After taking part in the first half of the Battle of Britain over southern England, the squadron moved to Kirton-in-Lindesy, North Lincolnshire, before finally moving over to Cranage to act as a night fighter squadron in defence of North-Western England at the end of November.

The issue of their impending arrival, prompted a memo to be sent to the Air Officer Commanding No.9 Group Fighter Command on 30 October. As the School was now running night navigation training it was feared that identification between the two sections would clash and therefore the potential for yet more accidents was huge. Overcrowding was also a problem with the School personnel having to be accommodated off site in local houses creating room for 85 Squadron personnel. In the 2001 Census for Byley Village [situated next to the airfield] the population stood at 202, compare this to the document ‘Further Reconnaissance of Cranage’ dated early November 1940 which shows that the airfield population had already reached 1,200 and was still climbing [1,800+ was the highest figure].

One idea would be to house fighter squadron on the east side of the airfield with its own operations and administration hierarchy. Having identified this as an option, the Station Commander also noted that the large property [Cranage Hall] situated approximately a mile east of the airfield could accommodate 70 personnel and with additional huts in the grounds it could be home to many more.

While the finer details of where to put extra personnel and aircraft continued, construction at Cranage continued and at this time the fuel storage was still to be completed. One 8,000 gallon tank had been acquired and for now had been allocated to Motor Transport for petrol though there were concerns that the fighter squadron might take priority of it for their 100 Octane fuel. The station was already using approximately 1,000 gallons every 24 hours, this was done using four mobile tankers which had only recently been obtained.

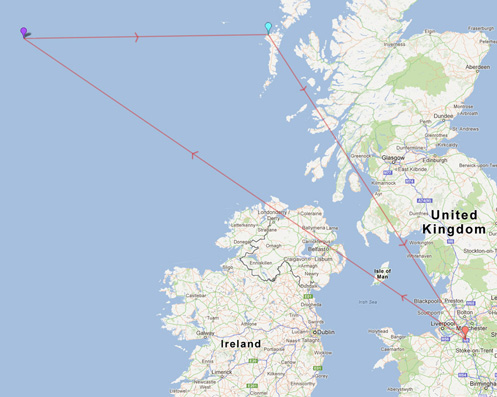

The night fighter squadron would, it was assumed, take up the protection of Liverpool and Manchester under the cover of darkness. At this time both cities were being heavily bombed and the damage to buildings and infrastructure as well as the civilian casualties meant action was required immediately. The patrol area would be from Shrewsbury, to the Great Orme, to Preston and over to Sheffield, not that dissimilar and area to the training flight area covered by No.2 S.o.A.N. who themselves were planning to operate 24 Anson aircraft each night on 2 to 2½ hour flights.

The night fighter squadron would, it was assumed, take up the protection of Liverpool and Manchester under the cover of darkness. At this time both cities were being heavily bombed and the damage to buildings and infrastructure as well as the civilian casualties meant action was required immediately. The patrol area would be from Shrewsbury, to the Great Orme, to Preston and over to Sheffield, not that dissimilar and area to the training flight area covered by No.2 S.o.A.N. who themselves were planning to operate 24 Anson aircraft each night on 2 to 2½ hour flights.

The image, right, is an approximate representation of the Cranage night fighter patrol area.

To reduce the chance of friendly fire from the fighter squadron the School's Anson aircraft were fitted with Identification Friend or Foe [I.F.F.], and formation lights. The former, an identification system designed for command and control, enabling interrogation systems to identify aircraft as friendly while also determining the bearing and range from the interrogator. A problem with the system is that it can only identify friendly targets, if the interrogator does not receive a reply or if it receives an invalid reply then the object is not accepted as friendly, but it is not positively identified as a foe. There are many reasons for friendly aircraft not to reply to IFF, such as battle damage, equipment failure or loss of/wrong encryption keys. School pilots were instructed not to fly above 5,000 feet and each of 9 Group's sector stations were informed of training routes, which was in turn was relayed to the fighter pilots. To make matters worse Cranage is situated close to the Pennines, to the east, and the Welsh hills to the west with large Barrage Balloon sites to the north and south, all offering plenty for trainees and fighter pilots alike to worry about.

These were not matters that would be resolved overnight, and so, on 1 December 1940, No.29 Squadron detached a Flight of Blenheim F1’s from Digby, Lincolnshire. On 8 December, 5 Hurricanes of No.422 Flight [special unit] arrived from Shoreham, Sussex followed on 10 December by a Flight of Defiant aircraft belonging to No.307 Squadron fresh in from Jurby, Isle of Man. One week later on 17 December, No.422 Flight was reformed as the third generation No.96 Squadron, with extra Hurricane and Defiant aircraft being delivered in February 1941.

Almost immediately, it was decided that No.96 Squadron should be split into A and B flights alternating between Cranage and Squires Gate at Blackpool allowing as large a patrol area as possible. At Cranage the squadron was located on the north east side of the airfield allowing them to operate with minimal disruption to the School. A year later in October 1941 No.96 Squadron moved to the recently completed R.A.F. Wrexham, complete with its hard runways, it would still take until April 1942 before Cranage finally received the P.S.P. that it was promised on New Years Eve 1940.

All material on the web site is covered by copyright © 2010 - 2016